January began settled and cloudy with mild weather for most of the month except for a cold, wet period towards the end of the month. Consequently, the provisional UK mean temperature in January was 5.6oC, which is 2.0oC above the long-term national average (1981-2010). Regionally temperatures were above average across all regions in January and the preceding 3 months (November 2019 – January 2020).

Overall, UK rainfall was as expected in January. However, this varied widely between regions and considerably above average in north and west Scotland, and below average in Northern Ireland and the east of England. For the preceding three months regional rainfall showed a pattern of above average in more southern regions of the UK.

Liver Fluke

Animals which have grazed high-risk “flukey” pastures (areas of wet/boggy grazing and those adjacent to permanent water bodies) towards the end of last season may be affected by chronic fasciolosis caused by adult flukes (Figure 2). Such infections may present with few or no obvious signs, yet can negatively affect health, welfare and productivity through reduced growth rates, fertility, milk yields etc. Chronically infected sheep and cattle can remain infected for months or even years if untreated, making them an important source of pasture contamination for the coming season.

Figure 2: Chronic fasciolosis is caused by adult flukes residing in the bile ducts of the liver. Such infections may show no obvious signs of disease, yet can have a profound negative impact on health, welfare and productivity.

Advised actions include:

- Monitoring for signs disease:

- General dullness, anaemia and shortness of breath

- Rapid weight loss, fluid accumulation (bottlejaw)

- Identify “flukey” pastures (wet or boggy areas) and avoid grazing until later into the current season.

- In the absence of obvious signs, as is often the case with chronic infection, consider diagnostic testing.

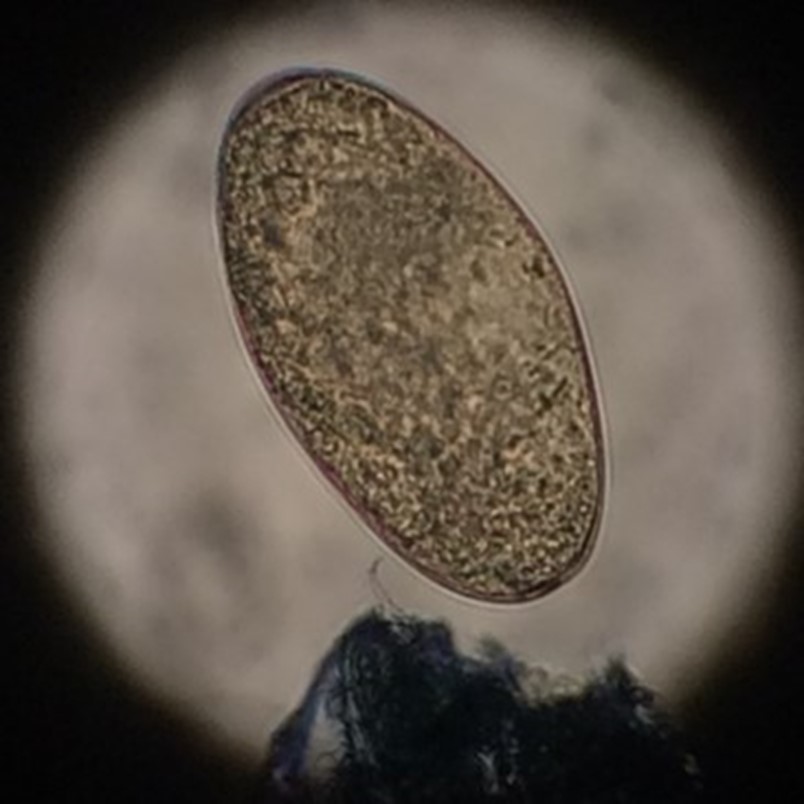

- Fluke egg counts can be used to diagnose chronic infection using faecal samples from individual animals, or to determine the infection status in groups of animals with a pooled sample composed of faecal samples taken from ten animals representative of the overall group (Figure 3).

- Abattoir feedback can provide useful information with respect to fluke infection status (Figure 2).

Figure 3: Chronic fluke infection can be identified through egg sedimentation using either individual or pooled faecal samples.

Where fluke infection is identified:

- Treatment with triclabendazole is recommended for acute disease, as this is the only product effective against both adult and immature stages of the parasite.

- If treating for chronic infection, due to concerns over emerging drug resistance consider alternative products to triclabendazole.

- Closantel, nitroxynil, oxyclozanide and albendazole (at the higher dose rate for liver fluke) are all effective against adult flukes, the cause of chronic fasciolosis.

- Activity of these products against juvenile and adult flukes varies. Please see cattle flukicides and sheep flukicides guides for more information.

- Ensure correct dosing is based on bodyweight, and consider testing for treatment efficacy through pre- and post-treatment diagnostics.

- For more information about how best to implement the various treatment and control options and conduct efficacy testing on your farm, please speak to your vet.

- Closantel, nitroxynil, oxyclozanide and albendazole (at the higher dose rate for liver fluke) are all effective against adult flukes, the cause of chronic fasciolosis.

SCOPS press release concerning 2% Moxidectin injectables

A press release issued by SCOPS group in collaboration with Zoetis Animal Health in February highlights the responsible practices for use of 2% injectable moxidectin formulations due to their importance for controlling of both roundworms and ectoparasites such as sheep scab. For more information, the press release can be read in full here.

Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE)

For pregnant ewes, past advice given concerning the “periparturient rise” (PPR) in worm egg counts around lambing time was to treat all ewes to reduce pasture larval contamination. However, recent work conducted by SCOPS has shown blanket treatment of ewes at this time with anthelmintics of any kind has very little effect on subsequent infection in lambs. Consequently, to reduce selection for anthelmintic resistance it now advised that treatment at this time is restrict to ewes in poor body condition, immature shearlings and ewe lambs only.

Nematodirosis

It is important to consider nematodirosis (disease caused by Nematodirus battus) in your lambs at this time of year. Unlike other gut nematodes, Nematodirus infection passes directly from one season’s lamb crop to the next. Pastures may become highly infective in a short space of time due to favourable conditions leading to mass hatching and emergence of infective stage larvae. If this mass emergence or “peak hatch” occurs at a time when lambs are starting to graze extensively, typically around 6-12 weeks of age, this can lead to widespread and severe disease characterised by sudden onset diarrhoea, dehydration and death. Affected animals normally present with heavily soiled back ends, lack of appetite and a profound thirst (Figure 4). It is therefore important to identify potentially contaminated pastures and avoid grazing lambs on these during peak risk periods for disease. SCOPS produces a risk forecast for nematodirosis to help predict when “peak hatch” periods are likely to occur. The relatively mild start to the year is likely to have allowed some development of these parasites on pasture already. If the conditions persist peak hatch may occur earlier in some parts of the UK than would be typically expected. It is strongly advised you consult these forecasts (available now) and plan your grazing and parasite control strategies accordingly.

Figure 4: Nematodirus battus infection can cause sudden onset, severe diarrhoea in first season lambs often with characteristic soiling around the back end.

Advised actions include:

- When treating PPR in ewes, SCOPS currently recommend limiting treatments to thin and shearling ewes.

- For nematodirosis in lambs:

- Identify high risk pastures, namely those grazed by the previous season’s lambs, and avoid grazing the current season’s lambs here during peak risk periods.

- Consult the SCOPS Nematodirus forecast to determine when the peak risk period is likely to be in your area and monitor for signs of disease.

- Where disease occurs treatment with group 1-BZ is usually effective. However, reports of treatment failures have been reported in the UK.

- It is therefore essential to ensure correct dosing by weight and administration using correctly calibrated drenching equipment.

- Consider egg counts 7-10 days post-treatment to confirm efficacy (Figure 5).

- Where treatment failure is suspected, please seek veterinary advice.

- For more information, please speak to your vet or RAMA (SQP) and see the ”SCOPS” group guidelines.

Figure 5: Faecal egg counts are a useful way of evaluating various parasitic infections. This method can be used to identify Nematodirus eggs (N.b) and those of other PGE-causing roundworms (Str.) as well as coccidial oocysts (arrows).

Coccidiosis

Another parasitic disease of importance in growing lambs is coccidiosis. This disease is caused by protozoal parasites (Eimeria spp.) causing gut damage. Signs of disease typically occur around 4-8 weeks of age and are characterised by anorexia, weight loss, diarrhoea (with or without blood) and death in severe cases. Coccidiosis results from a rapid accumulation of infective “oocysts” in the environment, which can occur both indoors and at pasture. This is commonly associated with high intensity husbandry systems and stress factors such as poor colostrum supply, high stocking densities, adverse weather conditions at wet muddy paddocks previously grazed by sheep and/or extended housing periods.

Due to the similar presenting signs and age ranges of affected animals, in grazing lambs it is important to determine whether Eimeria or Nematodirus infection is present and causing disease. Concurrent infection with both parasites is not uncommon, potentially leading to greater disease severity.

Advised actions include:

- Monitoring for signs of disease

- Routine worm egg counts can also be used to evaluate oocyst numbers (Figure 5).

- When considering treatment, further testing to determine whether oocysts present are from a pathogenic Eimeria is also advised.

- Reduction of stocking densities, batch rearing of lambs by age and avoidance of heavily contaminated pastures/premises can reduce risk of disease outbreaks.

- A number of anticoccidial products including feed medication are available for both prevention and treatment of coccidiosis. For more information on these, please speak to your vet or RAMA (SQP).

New COWS group guidelines released

The working group for Control of Worms Sustainably in cattle (“COWS”) have recently updated their guidelines on control of roundworms, lungworms, liver and rumen fluke and ectoparasites. Please visit the COWS group website to see these new updated guidelines in full.

Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE)

Calves and youngstock entering their first or second grazing season are at greatest risk of PGE (Figure 6). It is therefore important to plan around these animals when devising an effective, sustainable parasite control plan for your farm. The COWS group currently recommend one of two options. Choice of strategy is largely dependent upon individual farm objectives and the feasibility of their implementation:

- Strategic anthelmintic treatments. This option requires the use of anthelmintics treatments early in the grazing season, typically within 3 weeks of turnout, to reduce further pasture contamination with subsequent follow up treatments depending upon the type of treatment used up to mid-July by which time the over-wintered larval populations should have declined to insignificant levels. This control strategy assumes treated cattle will initially be set-stocked, but may be moved to safe pastures (e.g. hay or silage aftermaths) later in the grazing season as these become available. Strategic treatments include administration of a bolus wormer at turnout or repeated administration of shorter duration group 3-ML products at a 6-8 week intervals. This approach will lead to on-farm selection pressure for anthelmintic resistance. Efficacy should therefore be monitored by diagnostic testing and performance indicators such as weigh-gain, and practices reviewed if found to be sub-optimal.

- Therapeutic treatments. This option aims to avoid use of anthelmintics unless needed. This is achieved through close monitoring of animals for egg counts and performance indicators for early signs of infection and ill-thrift and treating before clinical disease occurs, or is believed to be an imminent risk. Whilst reducing selection pressure for anthelmintic resistance, this approach increases the risk of sub-clinical infection and production losses and will not prevent build-up of pasture larval burdens throughout the grazing season. Where available, this approach can make use of pasture rotation to prevent animals being exposed to a significant build-up of infective larvae later in the grazing season, although this needs to be planned well in advance to ensure safe grazing options are available when needed.

Figure 6: PGE in cattle causes diarrhoea and up to a 30% reduction in the growth rates of youngstock. Commonly affected animals include growing dairy heifers in their first grazing season (left) and weaned autumn-born suckler calves in their second grazing season (right).

Lungworm

On farms with a history of lungworm infection, vaccination offers a valuable tool for protection against disease in calves (Figure 7). Since the lungworm vaccine is live, it must be purchased fresh ahead of each grazing season. Planning and ordering the number of doses required for your farm well in advance is therefore advisable.

- All calves over 8 weeks old entering their first grazing season should be given two doses of lungworm vaccine four weeks apart, with the second dose being given at least two weeks before turnout.

- In some instances, such as where anthelmintic regimes may have prevented full immunity being acquired over the previous grazing season, a further one off vaccination may be recommended in is sometimes recommended.

- For more information, please speak to your vet or RAMA (SQP) and see “COWS” group guidelines.

Figure 7: Lungworm infection can be a very serious problem for youngstock. On farms with a history of disease vaccination can be hugely valuable in reducing disease incidence and severity, but must be ordered and planned well in advance.