Weather report

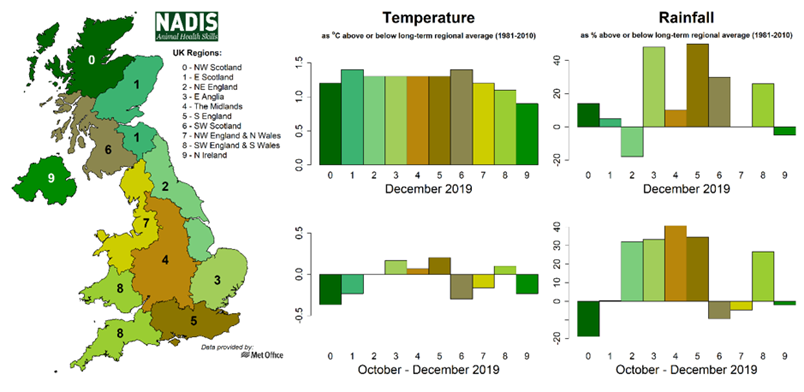

Figure 1: Temperature and rainfall by region for previous months.

December 2019 started with some periods of heavy rainfall, but became drier towards the end of the month. The month was also much warmer than usual, with fewer frosts than expected at this time of year. The provisional UK mean temperature was 5.1oC, 1.3oC above the long-term average (1981-2010). This was observed across all regions in December, although the mean temperatures for the previous 3 months (October-December 2019) was generally comparable to the long-term average. UK rainfall was 116% of the long-term average overall, but varied considerably by region, with very high levels of rainfall compared to the long-term regional averages observed in the midlands, east and south of England and south of Wales, whilst rainfall for the previous 3 months was observed to be above average in East Anglia, the south of England and Wales and western Scotland.

Review of flock health plan

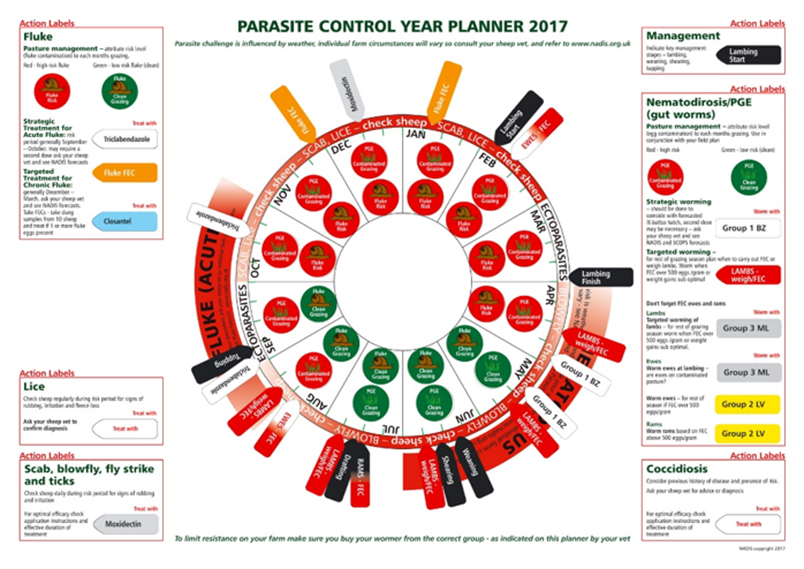

Winter provides a good opportunity to review and plan on-farm parasite control strategies ahead of coming grazing season. Preparation will help you to develop a robust yet practical programme to reduce disease burdens, costs and selection for anthelmintic resistance. Please speak to your vet or SQP about devising a parasite control plan to work for your farm. More information on sustainable parasite control is sheep and cattle can be found on the “SCOPS” and “COWS” websites, and cattle and sheep-specific parasite control planners are available through NADIS (Figure 2), which can help devise and visualise your plan for the coming year. Important issues to bear in mind include:

- Seasonal risk and farm history. Different parasites cause problems at different times of year and under different conditions. Considering specific issues you have encountered in the past and when these occurred can help you plan for the future. The NADIS parasite forecast can be a useful resource to highlight specific seasonal and regional parasite risks.

- Identify at-risk animals. Generally, younger animals are often more susceptible to parasitic diseases, particularly calves and lambs entering their first (and potentially second) grazing season.

- Choice and rotation of anthelmintics. Make sure you are familiar with the products available, their active ingredients and indications for their use. Appropriate choice of wormers and product rotation will help reduce selection for anthelmintic resistance on your farm.

- Bio-security and quarantine measures. Holding and quarantine treatment of purchased animals prior to turnout on to pastures will help prevent introduction of anthelmintic resistance on to your farm.

- Diagnostic and performance testing. Ideally, routine diagnostic testing should be at the centre of any sustainable parasite control scheme. Diagnostic tests such as worm egg counts provide useful information when deciding treatment and pasture management options. Performance testing can also help provide a more targeted approach to worm control through identification of those animals worst affected. If used correctly, diagnostics and performance monitoring can identify issues before they become severe, reduce the amount of anthelmintics required and improve timing of dosing, ultimately reducing costs and boosting productivity.

- Identify “safe” and “contaminated” grazing. Contaminated pastures are those grazed previously by infected animals, including pastures grazed the previous season. Safe pastures are those which have not been grazed previously, such as freshly seeded leys, and silage and hay aftermaths. Pastures previously grazed by sheep are generally safe for cattle and vice versa with respect to roundworms, although it is important to note this is not necessarily the case with liver fluke. Planning of pasture management and rotation should be planned in conjunction with testing, performance monitoring and treatment regimens.

- Other work planned through the year. Incorporating parasite control into other seasonal activities such as spring turnout, shearing, winter housing etc. can help implementation. An important aspect of for any successful parasite control plan is that it is adhered to. Simplifying and doubling up with other activities where possible will help facilitate this.

Figure 2: Cattle and sheep specific parasite control planners are available through NADIS and can help develop a sustainable, practical on-farm strategy.

Fluke

Despite the relatively mild weather experienced in November and December, development and emergence of liver fluke on pastures is likely to have arrested at this time, since development of the free-living stages of liver fluke and its intermediate snail host require average temperatures at or above 10oC. However, previously contaminated pastures will remain infective over winter and into the following season, meaning continued vigilance for signs of disease in animals grazing “flukey” pastures (areas of wet/boggy grazing and those adjacent to permanent water bodies) is necessary. Animals which have previously grazed high risk pastures towards the end of last season may be affected by chronic fasciolosis. This form of the disease is caused by adult flukes residing within the bile ducts. Such infections can affect large numbers of animals, often presenting with few or no obvious signs of disease yet negatively affecting health, welfare and productivity with reduced weight gain, milk yields and fertility in both sheep and cattle. Furthermore, chronically infected sheep and cattle can remain infected for months or even years if untreated, making them an important source of pasture contamination for the coming season.

Advised actions include:

- Monitoring for signs disease:

- General dullness, anaemia and shortness of breath

- Rapid weight loss, fluid accumulation (bottlejaw)

- Sudden death in heavy acute infections

- In the absence of obvious signs, as is often the case with chronic infection, consider diagnostic testing.

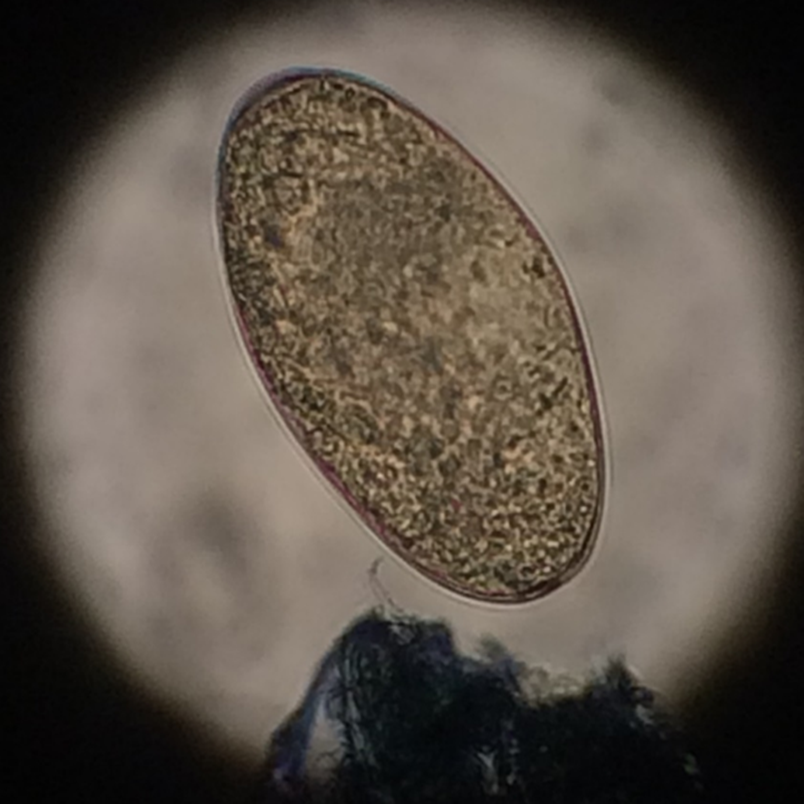

- Fluke egg counts can be used to diagnose chronic infection using faecal samples from either individual animals, or to determine infection status in groups of animals a pooled sample from ten animals representative of the overall group (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Chronic fluke infection can be identified through egg sedimentation using either individual or pooled faecal samples.

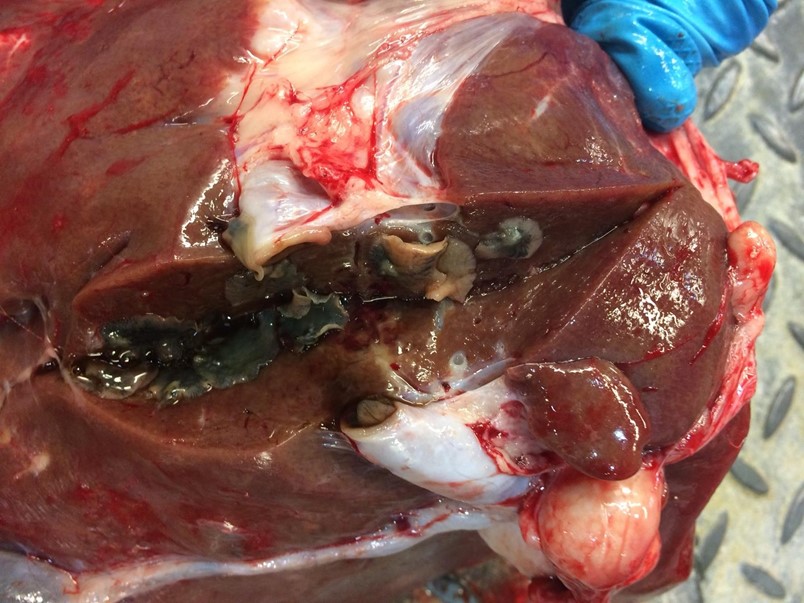

- Where available, abattoir feedback can provide useful information with respect to fluke infection status (Figure 4)

- For more information on diagnostic options and sampling, please speak to your vet.

- Routine clostridial vaccination to prevent Black disease and should be considered if not already in place.

Figure 4: Getting abattoir feedback can be a useful way of identifying and monitoring fluke infection on your farm (Photo credt: Jose Del Puerto DVM OV)

Where fluke infection is identified:

- Treatment with triclabendazole is recommended for acute disease, as this is the only product effective against both adult and immature stages of the parasite.

- In housed animals consider use of a product other than triclabendazole to treat chronic infection due to concerns over emerging drug resistance.

- Closantel, nitroxynil, oxyclozanide and albendazole (at the higher dose rate for liver fluke) are all effective against adult flukes, the cause of chronic fasciolosis.

- Activity of these products against juvenile and adult flukes varies (see cattle flukicides & sheep flukicides)

- If treating cattle with an adulticide product like closantel, the “COWS” group recommend repeated or delayed treatment at 6-7 weeks post-housing (cattleparasites.org).

- For sheep, the “SCOPS” group suggest using closantel or nitroxynil at 3 weeks post housing, with a further treatment to kill any residual adult parasites in the spring (scops.org).

- Closantel, nitroxynil, oxyclozanide and albendazole (at the higher dose rate for liver fluke) are all effective against adult flukes, the cause of chronic fasciolosis.

- Due to concerns over emerging drug resistance, ensure correct dosing is based on bodyweight, and consider testing for treatment efficacy through pre- and post-treatment diagnostics.

- For more information about how best to implement the various treatment and control options and conduct efficacy testing on your farm, please speak to your vet.

Sheep - Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE)

For pregnant ewes, past advice given concerning the “periparturient rise” (PPR) in worm egg counts around lambing time was to treat all ewes to reduce pasture larval contamination. However, recent work has shown blanket treatment of ewes at this time with anthelmintics of any kind has very little effect on subsequent infection in lambs. Consequently, to reduce selection for anthelmintic resistance it now advised that treatment at this time is restrict to ewes in poor body condition, immature shearlings and ewe lambs only.

For Nematodirosis (disease caused by Nematodirus battus), pastures can become highly infective in a short space of time with mass hatching and emergence of infective stage larvae. This can lead to widespread and severe disease in growing lambs, typically 6-12 weeks old (Figure 4). SCOPS produces a risk forecast for Nematodirus based on local climatic conditions from mid-February onwards to help predict when “peak hatch” periods are likely to occur. Usually this occurs from mid-March/April onwards, but can happen sooner under favourable conditions, so vigilance is advised.

Figure 5: Nematodirus battus infection can cause sudden onset, severe diarrhoea in first season lambs often with characteristic soiling around the back end.

Advised actions include:

- When treating PPR in ewes, SCOPS currently recommend limiting treatments to thin and shearling ewes.

- Faecal egg counts may also be useful in informing targeted selective treatments.

- For Nematodirosis in lambs:

- Identify high risk pastures (those grazed by the previous season’s lambs) and avoid grazing these during peak risk periods.

- Consult the SCOPS Nematodirus forecast to determine peak risk period.

- Monitor for signs of disease.

- For more information, please speak to your vet or SQP and see the ”SCOPS” group guidelines.

Scab (mite) and louse infestations can become a significant problem in sheep flocks over the autumn and winter months, typically September-April. Whilst the signs of scab and louse infestations are similar, treatment options may differ considerably since scab mites live on the skin, whilst lice reside within the fleece. This makes diagnosis an important first step towards treatment.

Sheep scab is caused by psoroptic mites (Psoroptes ovis). Infestations cause loss of condition, secondary skin infections and potentially death if not treated. When examined, the fleece may be wet, sticky and yellow due to serum discharge and the skin may become thickened and corrugated. Studies show scab mites can remain infective in the environment for up to 17 days. Consequently, fields, sheds and pens where infected sheep have been kept and handled should be considered a potential source of infection to other sheep during this period.

Louse infestations in the UK are mainly caused by chewing lice (e.g. Bovicola ovis) and may present in a similar, but less severe way to scab. Thin sheep tend to be most greatly affected, with widespread louse infestations often indicative of another underlying problem within the flock.

Advised actions include:

- Monitor for signs of disease:

- Severe itching, wool loss, restlessness, biting and scratching of affected areas and weight loss or reduced weight gain.

- Affected sheep may show disturbed grazing patterns, kicking at their chest with their hind feet and/or rubbing themselves against fence posts.

- To reach a diagnosis:

- Microscopic examination of skin scrapings from suspected animals allows detection of mites, whilst lice can be observed in wool samples taken from affected areas with the naked eye and confirmed by microscopy (Figure 6)

- There is also an ELISA test to detect antibodies against sheep scab mites in blood samples.

- For more information concerning diagnosis, please speak to your vet.

- It is important to remember sheep scab is notifiable in Scotland.

Figure 6: Psoroptic mites (left) can be identified from skin scrapings, whilst louse infestations can be confirmed in affected fleece (right). Photos courtesy of Dr Joseph Angell.

Where treatment is required:

- Injectable macrocylic lactone (3-ML) products are effective against sheep scab with varying periods of protection. For more information concerning treatment with 3-MLs please speak to your vet or SQP.

- It is important to remember that 3-MLs are also an important class of anthelmintics and, if used, should be considered as a roundworm treatment also.

- There is evidence showing the emergence of resistance in scab mite to group 3-MLs in the UK. It is therefore important to ensure correct diagnosis and treatment protocols are adhered to, and that veterinary advice sought if treatment failure is suspected.

- Louse infestations can be controlled with topical products containing synthetic pyrethroids. These products are most effective on shorn sheep.

- Plunge dipping with diazinon is effective against both scab and louse infestations.

Cattle - Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE)

Growing cattle not dosed appropriately at housing following their first or second grazing season may be at risk from type-2 ostertagiosis. This condition results from the triggered mass emergence of encysted larval infections in late winter/ early spring. Such infections cannot be assessed accurately by worm egg count. Risk should instead be determined by considering previous grazing and treatment history.

Advised actions include:

- Identifying at risk animals based on age and grazing history

- Treatment with a product containing either a 3-ML or 1-BZ anthelmintic, as these are effective against encysted larval stages of Ostertagia.

- Be vigilant for signs of type-2 disease in youngstock:

- Sudden onset profuse, sometimes intermittent, diarrhoea (Figure 7)

- Loss of weight and body condition

- Blood testing (plasma pepsinogen levels) can also be useful in aiding diagnosis.

- For more information, please speak to your vet or SQP and see the “COWS” group guidelines.

Figure 7: Young stock not dosed in the autumn may be at risk from type-2 ostertagiosis towards the end of the housing period.

Lungworm

On farms with a history of lungworm infection, vaccination offers a valuable tool for protection against disease in calves (Figure 8). Since the lungworm vaccine is live, it must be purchased fresh ahead of each grazing season. Planning and ordering the number of doses required for your farm well in advance is therefore advisable.

- All calves over 8 weeks old entering their first grazing season should be given two doses of lungworm vaccine four weeks apart, with the second dose being given at least two weeks before turnout.

- In some instances, such as where anthelmintic regimes may have prevented full immunity being acquired over the previous grazing season, a further one off vaccination is sometimes recommended for animals entering their second grazing season.

- For more information please speak to your vet or SQP and see “COWS” group guidelines.

Figure 8: Lungworm infection can be a very serious problem for youngstock. On farms with a history of disease vaccination can be hugely valuable in reducing disease incidence and severity, but must be ordered and planned well in advance.

Cattle Ectoparasites

Louse and mite infestations in cattle are not uncommon during winter housing (Figure 9). Generally low level infections are not of major concern, but heavy louse infestations may indicate an underlying management or health issue and, where sucking lice are present, may cause anaemia compounding existing problems.

A range of pour-on and spot-on synthetic pyrethroid products are available with efficacy against lice, whilst group 3-ML pour-on preparations are also effective, with injectable group 3-ML preparations effective against sucking lice.

A relatively small number of injectable and pour-on group 3-ML based products are available in cattle against mange mites, with some and pour-on synthetic pyrethroids preparations also effective. Where mange infestations are a cause for concern, please seek veterinary advice concerning further diagnosis, as the type of mite causing disease will help to inform treatment choice. Psoroptic mange in particular can cause severe disease (Figure 9) and in outbreaks treatment is usually necessary for all in-contact animals to achieve elimination.

Where treatment of ectoparasites is indicated, it is advisable to follow up with further examination and diagnostic testing. Resistance to synthetic pyrethroids has been identified in lice, whilst treatment of psoroptic mange with group 3-MLs can produce varied results often requiring multiple treatments. It is also important to note that scab mites can live in the environment for 2-3 weeks, meaning good disinfection and biosecurity measures are important for control. For more information on ectoparasite control in cattle please speak to your vet or SQP, and see the “COWS” guidelines.

Figure 9: Ectoparasites (louse and mite infestations) in housed cattle usually produce only mild, self-resolving signs (top). However, some parasites and circumstances, such as psoroptic mange (bottom) can lead to more severe disease and the need for appropriate treatment informed by diagnosis.